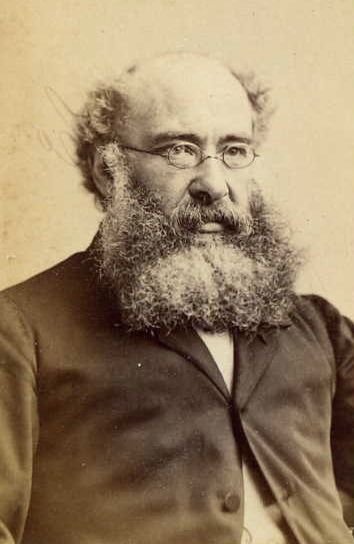

Anthony Trollope, 1815 - 1882

Having recently finished Barchester Towers by Anthony Trollope, I spent today gathering and jotting down impressions of one character in this novel, published in 1857.

The Rev. Septimus Harding is an Anglican clergyman, musician, loyal father, and minor ecclesiastical official in the fictional county of Barsetshire, England. Trollope began his Chronicles of Barsetshire series with The Warden, in which Mr. Harding as protagonist defended his honor by giving up his post as warden at Hiram’s Hospital. Barchester Towers, perhaps Trollope’s best-known work, is the second volume in the series. I’d say Mr. Harding’s daughter, the lovely and wealthy widow Eleanor Bold, is the protagonist in this one as she fends off two creepy suitors and gains the one she wanted all along. But her father’s understated presence remains powerful and, for this reader, inspiring.

Trollope as narrator makes clear that “Mr. Harding was by no means a perfect character.” In fact, due to “his indecision, his weakness, his proneness to be led by others, his want of self-confidence, he was very far from being perfect.” So why do I want to remember him, to carry away as clear an image of him as I can?

To answer this question, I used my Kindle’s search capability throughout the day to review all 416 mentions of “Harding” in the novel. I was looking for passages which directly characterized Mr. Harding, especially in his extended conflict with the despicable Obadiah Slope. Here is what I found, mostly presented as direct quotes:

It was not his practice to say much evil of anyone.

The whole tendency of his mind and disposition was opposed to any contra-assumption of grandeur on his own part, and he hadn’t the worldly spirit or quickness necessary to put down insolent pretensions by downright and open rebuke.

He had never rated very high his own abilities or activity.

He gave his enemy the benefit of the doubt, and did not rebuke him.

He winced at the idea of the press, having been badly burned in The Warden by a run-in with The Jupiter, described by the narrator as “that daily paper which, as we all know, is the only true source of infallibly correct information on all subjects.”

He did not like being called lily-livered, and was rather inclined to resent it.

He doubted there was any true courage in squabbling for money.

It was customary for him in times of sadness to have recourse to the following old trick: He began playing some slow tune upon an imaginary violoncello, drawing one hand slowly backwards and forwards as though he held a bow in it, and modulating the unreal chords with the other.

His authority over Eleanor ceased when she became the wife of John Bold. He had not the slightest wish to pry into her correspondence.

When everyone falsely believed that Eleanor planned to become, dread thought, Mrs. Obadiah Slope, Mr. Harding believed the rumor to be false but even if true, the father would still open his heart to his daughter and accept her as she present herself, Slope and all.

Peculiar to Mr. Harding was a womanly tenderness. His feelings towards his friends were, that while they stuck to him he would stick to them; that he would work with them shoulder to shoulder; that he would be faithful to the faithful. He knew nothing of that beautiful love which can be true to a false friend.

On happily discovering that Eleanor had absolutely no intention to consider Mr. Slope as a suitor, Mr. Harding was by no means sufficiently a man of the world to conceal the blunder he had made. He could not pretend that he had entertained no suspicion; he could not make believe that he had never joined the archdeacon in his surmises. He was greatly surprised, and gratified beyond measure, and he could not help showing that such was the case.

On being offered the title of dean, Mr. Harding refused the proffered glory, again and again alleging that, at nearly 65 years of age, he was wholly unfitted to new duties.

He slowly, gradually, and craftily propounded his own new scheme. Why should not Mr. Arabin (by now revealed as Eleanor’s true love and fiance) be the new dean?

With obstinacy, Mr. Harding could adhere to his own views in opposition to the advice of all his friends. Nothing would induce the meek, mild man to take the high place offered to him, if he thought it wrong to do so.

Even after having been hounded out of the warden’s post at Hiram Hospital, he had continued to visit the old men living there. Lest they might conspire to receive the new warden, Mr. Quiverful, with aversion and disrespect, Mr. Harding made a special trip to the hospital to walk in, arm in arm, to ask from these men their respectful obedience to their new master.

He omitted, even in the more important doings of his life, that sort of parade by which most of us deem it necessary to grace our important doings.

Mr. Harding had no state occasions. When he left his old house, he went forth from it with the same quiet composure as though he were merely taking his daily walk; and now that he re-entered it with another warden under his wing, he did so with the same quiet step and calm demeanor.

Few men are constituted as was Mr. Harding. He had that nice appreciation of the feelings of others which belongs of right exclusivity to women.

“He be always very kind,” one of the old men said of Mr. Harding at the Hospital.

The good which Mr. Harding intended did not fall to the ground. All the Barchester world, including the five old men, treated Mr. Quiverful with the more respect, because Mr. Harding had thus walked in arm in arm with him, on his first entrance to his duties.

After the delightful work of gathering all these impressions of Mr. Harding, I am forced to revise my belief that he was not the protagonist of Barchester Towers. All the other characters and subplots seem to bend gently toward the revelation of his character and quiet triumph. And Trollope places the focus firmly on him with these concluding words of the book:

One word of Mr. Harding, and we have done.

He is still Precenter of Barchester, and still pastor of the little church of St. Cuthbert’s. In spite of what he has so often said himself, he is not even yet an old man. He does such duties as fall to his lot well and conscientiously, and is thankful that he has never been tempted to assume others for which he might be less fitted.

The Author now leaves him in the hands of his readers; not as a hero, not as a man to be admired and talked of, not as a man who should be toasted at public dinners and spoken of with conventional absurdity as a perfect divine, but as a good man without guile, believing humbly in the religion which he strives to teach, and guided by the precepts which he has striven to learn.

Thanks to this classic Victorian novel, I have a new way of nudging myself forward into my sixties. I already try to pause when agitated. Now after the pause, a question: “What would Mr. Harding do?”